|

Edward Peters, "Five

things every bishop needs to know about canon law", Catholic

Dossier (May-Jun 2001) 30-34. |

To make the claim that there are five

things every bishop needs to know about canon law suggests some possible assumptions that

should be considered prior to presenting the five points.

One assumption might be that bishops don’t already know the

five things I’ll recommend in this essay. But of course, making suggestions

does not imply that the recipient is unaware of the ideas. Given the Holy

See’s care in the selection of episcopal candidates, little in this essay will

come as a revelation to those men who have risen to the rank of diocesan bishop.

Instead, I hope that this formulation of certain suggestions might help bishops

to address canonical issues in a more fruitful way.

Others might suppose that, if bishops do not know and apply

the five things about canon law discussed herein, their ministries and dioceses

would be doomed to grave, perhaps irreversible, damage. To that let me observe

(none too originally) that if the Church were really at the mercy of any of the

various groups working within it (including canon lawyers), it would have

disappeared long ago. There is an element of that divine protection for the

Church as a whole that extends also to its legal system and its officers, a fact

which, provided it is not parlayed into an excuse for carelessness or abuse,

should be a consolation to us all.

Yet another assumption might grant that, while the aspects of

canon law presented here concern important matters in Church life, bishops ought

to be able to hand these matters over to knowledgeable and trustworthy

subordinates, freeing themselves to concentrate on more central ecclesial

issues. Canon law, after all, as John Paul II affirmed in his apostolic

constitution Sacrae disciplinae leges, “is not intended as a substitute

for faith, grace, charisms, and especially charity in the life of the Church (¶

16).”

Certainly it is true that in every governing structure, the

operations of its legal system eventually become the province of specialists,

and likewise that not every able leader in a society need be a legal scholar

thereof. In fact, for the Church’s first five centuries, no pope or bishop

could have told us clearly what canon law was. So much for its radical

necessity. But at the same time, no one denies that any leader, whether civil or

ecclesiastical, who has practical familiarity with the laws of that society,

will have an easier go of it. At a minimum, a firm grasp of the points outlined

below should aid bishops in recognizing canonical advisors worthy of their

confidence.

Having briefly addressed a few assumptions suggested by my

recommendations, I had planned to turn immediately to the specific points. But

almost the first thing I realized was that, had I been asked to write this essay

even five, but certainly ten, years ago, my first suggestion would have been

different from what it is today. The reasons behind this evolution are important

to consider.

Ten years ago, given ecclesiastical demographics, the typical

diocesan bishop in America would have been trained under the 1917 Code and,

although he might have had only a seminary sequence in canon law, nevertheless,

his canonical education would have highlighted the incredible length and breadth

of ecclesiastical issues treated by the Church’s legal system. Moreover, the

canonical concepts and categories he learned would have reflected those of St.

Pius X and Pietro Cardinal Gasparri. Of course, the Church and the world to

which it ministers underwent breath-taking changes in the decades following

1917, while codified canon law remained essentially unchanged until 1983. Thus,

to the bishop of ten years ago, my advice would have been something like:

“Please be conscious of the fact that the 1917 Code of Canon Law was

completely revised in 1983, and that consequently, many approaches to

ecclesiastical governance which were quite sound under the old code are

inadequate under the new.”

While I might have needed forgiveness for a certain temerity

then, the advice itself would have been basically sound. Paul VI had been

suggesting the same thing throughout the post-Conciliar canonical reform period.

The revised Code of Canon Law, he frequently observed, was going to require a

“novus habitus mentis” or a “new way of thinking,” in order to be

interpreted and applied correctly. John Paul II has made the same point

repeatedly throughout his lengthy pontificate.

Ten years ago, indeed, every practicing canonist had the

experience of advising bishops, (and not just bishops, of course, but they are

the focus of these remarks) who were clearly, however understandably, still

approaching issues treated under the 1983 Code with the assumptions and

techniques of the 1917 Code unduly in mind. Many times, to be sure, these were

minor matters which occasioned pleasant opportunities to explain some canonical

revisions; other times, though, the stakes were more serious, particularly when

bishops confronted problems requiring resort to sections of the law that had

undergone extensive revisions in the 1983 Code, major topics such as marriage

and annulments, the enhanced place of consultation and consent, substantive and

procedural rights of the faithful, and the implications of renewed

ecclesiastical subsidiarity.

It is Not as Hard as It Seems

Today, then, my suggestions must

take into consideration the fact that the number of diocesan bishops really

trained under the 1917 Code (as opposed to simply being ordained while it was

still technically operative) is small and dwindling. Moreover, canon law, and in

particular canon law training, suffered an inordinately long lame-duck period

due to the fact that the reform of the 1917 Code was announced in 1959, but was

not completed until 1983. The problem has, therefore, shifted from one wherein a

significant percentage of key ecclesiastical leaders received their formative

training under a legal system that had been abrogated, to one wherein many of

today’s ecclesiastical leaders received essentially no legal training

whatsoever.

Canon law was not exactly a popular academic major among

priests and seminarians, let alone laity, from the early 1960s to the 1980s.

Those relatively few who took anything more than, say, an overview course on

marriage law, generally had to study canon law from blurry photocopies of

various revision schemata constantly prefaced by comments like: "The most

recent proposal says . . ." or "One draft under consideration holds . .

." Against, then, the already aggravating backdrop of a pervasive post-Conciliar

antinomianism, young clerics saw that the days of the 1917 Code (in their minds,

a thick document indistinguishable from canon law in general) were clearly

numbered, while the absence of canon law textbooks in the classroom further

reinforced the perception that canon law was a discipline without clear

parameters. Canonistics, which till then had been a science shared by academe

and chanceries, became the nearly exclusive province of professors over

practitioners. Thus it happened that many men now ordained to the episcopacy

were first exposed to canon law during highly unsettled times, and they learned

to defer unnecessarily to canonical experts instead of attempting their own

informed reading of the text.

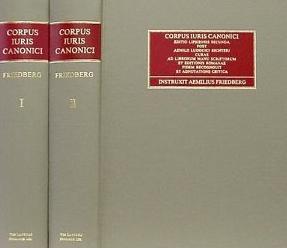

And so today, my first piece of advice to bishops concerning

canon law is simply this: Know that a venerable and complete legal system,

touching more or less directly every important aspect of Church life, exists in

one, comprehensive volume, and that regardless of your academic formation in

canon law, you can make effective use of this law in your ministry, perhaps in

ways you have never imagined before. I have worked with bishops who, while not

trained as canonists, nevertheless had read Church law carefully, so I know they

were in a much better position than were others to understand and make wise

selections from among the legitimate options their canonical advisors could

later set before them.

The second thing that every bishop needs to know about canon

law flows from the first and offers reinforcement of it. It too requires some

prefacing remarks.

The Catholic Church’s attitude toward canon law rests on

fundamentally very different foundations than does, say, the Anglo-American

attitude toward civil law. Grounding the American attitude toward law is the

idea that law is meant, in large part, to restrict the degree of authority

government has over our lives and that its legitimacy flows from the consent of

the people being governed. All of this is good healthy Lockean and Jeffersonian

democracy.

But contrast this with the Catholic Church’s attitude

toward its law. The authority of popes and bishops does not depend in any sense

on the consent of the subjects they govern. Church history shows us, in fact,

that the rise of canon law in the Church was not occasioned by the needs of the

faithful to mark out liberties in the face of a power-grabbing hierarchy, but

rather was spawned by the needs of shepherds in Christ to facilitate the

exercise of their pastoral jurisdiction and, over time, to bring consciously to

bear the virtues of justice and equitable treatment upon those blessed enough to

be called children of God. From its most ancient roots, then, canon law has been

a plow in the hands of the hierarchy, not a sword in the hands of the faithful.

The Law Favors Bishops

Thus, when the Legislator set his

signature to the 1983 Code, his primary goal was to ensure that the institution

founded by Christ to lead men to God, and the popes and bishops who rule over

that Church, would have the administrative wherewithal to accomplish their task

in an upright way. From this flows my second suggestion: Bishops need to be

conscious of the fact that the Code of Canon Law, for very sound theological and

administrative reasons, was written in their favor, and that therefore, provided

they follow its sometimes tedious requirements, they will be upheld in virtually

any dispute occasioned by their decisions and actions.

Let’s consider briefly two concrete problems most bishops

have to face sooner or later: the removal of an unworthy pastor before the

expiration of his term, and the closing of an all-but-abandoned parish. Now, no

bishop walks into his office and says, “Gee, I feel like having some fun

today. I think I’ll get rid of crazy Fr. Bob and then, I dunno, maybe I’ll

close a couple parishes.” To the contrary, both tasks are approached with a

heavy heart. Either scenario can provoke fierce opposition from clergy and

faithful alike. Both offer numerous opportunities for the disregard of rights,

the abdication of duties, and general discord among the People of God. But both

are problems long faced by Church leaders and both are capable of being justly

addressed in accord with canon law.

In the case of the removal of an unworthy pastor, for

example, a sequence of 12 canons (cc. 1740-1752) guides bishops and pastors

alike in reaching an informed decision about the priest’s continuance in

ministry, but at every stage, the 1983 Code clearly reinforces the ultimate

authority of the bishop over the situation. Similarly, though admittedly without

the neat sequence of steps laid down for pastor removal cases, bishops and

faithful confronted with the possibility of closing a parish must have resort to

the canons on juridic personality (cc. 113-123), ecclesiastical property (cc.

1254-1310), and delivery of pastoral services (cc. 515-552) to understand how in

fairness a bishop may proceed in order to arrange parishes as he ultimately

deems necessary. While the results in either case might not be to everyone’s

liking, the very appearance of having acted in accord with law and justice can

help sow the seeds of rehabilitation in the case of a priest removed from

ministry, or of reconciliation among new parishioners in the case of faithful

who have lost their former parish. I shall return to the importance of bishops

being seen as trying to do justice in my final suggestion.

What Goes on in the Tribunal

At this point, let me shift the focus away from internal matters that are of

interest primarily to Catholics, and look directly at an area in which many

non-Catholics, and sometimes secular society itself, maintain an ongoing

interest. I speak of marriage and annulments. To my third suggestion simply: Every diocesan bishop needs to understand the canons, both

substantive and procedural, under which his tribunal operates.

Tribunal work is an area in which non-canonist bishops seem

especially reluctant to enter. That’s understandable. Marriage canon law is

ancient and complex. It has spawned more canonical literature than all other

topics in canon law combined, making it a daunting field for non-degreed

persons. Diocesan tribunals operate under serious time and resource restraints,

and are often subject to extensive public criticism from the faithful, the

secular media, and other agencies in the Church, even though tribunals, due to

privacy constraints, can rarely reply with the kind of detail needed to address

such concerns. And, as if all those factors discouraging direct episcopal

involvement in tribunals were not enough, the basic facts on which most actual

annulment petitions turn are frequently depressing, tedious, saddening, and even

nauseating. I have offered the analogy of tribunals serving as crash

investigators, picking through the debris of wrecked marriages trying to figure

out what went wrong. There is nothing attractive about it, however important it

might be.

Despite these obstacles, canon law recognizes the diocesan

bishop as the chief judge in his diocese (c. 1419). It is difficult to see how

bishops can give effective leadership to their tribunals, at a time when they

might need it most, if they do not have an actual working knowledge of the

substantive canons on marriage and the procedural canons under which annulment

cases are heard. But even beyond that reason for deeper episcopal involvement,

tribunals are repositories of immense information on trends in marriage, or at

least trends in failed marriages. Any effort to communicate the insights of

tribunal personnel to those responsible for helping the bishop to develop

effective diocesan marriage preparation programs (and such coordinated efforts

are too few) would be greatly enhanced if the bishop himself thoroughly

understood what the tribunals are actually seeing and doing.

Advice or Consent

For my

fourth suggestion, I consider an

issue bishops face nearly every day and suggest that: Bishops need to understand

the greatly enhanced strengths, and the inescapable limitations, of the new

canonical requirements of consultation and consent as part of their regular

decision-making process. In a host of ways too numerous to list here, the 1983

Code, in contrast to the 1917 Code, requires bishops to seek advice sincerely

about, and at times to obtain consent to, many of their proposed actions.

This major change in approach comes as part of the general

tendency of the 1983 Code to grant local bishops much more decision-making

authority than was common under the former law. The new canons on consultation

and consent concretize the opportunity to make legitimate use of a wide range of

talents and expertise among the people of God in the local Church. But while

there is greater local autonomy for pastoral policies, there is also a greater

requirement to make sure such policies reflect local needs as opposed to

institutional preferences. Indeed, the scope of issues potentially involving

consultation or consent requirements is vast: ordination and continued ministry

of priests, most diocesan budget and finance issues, diocesan pastoral councils

and synods, distribution of parishes and numerous clergy matters, renovation of

churches, enactment of disciplinary norms, supervision of schools and, well, the

list just goes on and on.

But, to consider only the most basic distinction here,

consultation does not mean consent (c. 127) and bishops need to know in advance

which they are seeking, if only to explain to those with whom they are

conferring the differing expectations attached to their discussions.

Particularly in America, we are inclined to see committees and councils as

policy-making bodies, which under canon law they rarely are. At many times in

the past, such groups have had to be reigned in, a difficult task obviously, and

one that might not have been necessary if all those involved, including the

bishop, had been better able to articulate the theology and practical aspects of

the 1983 Code’s greatly enlarged emphasis on consultation and consent in

Church life.

An Aid to ‘Enforcement’

My fifth suggestion, like those above,

will not be news to bishops, but rather, affords them an opportunity to consider

how canon law is an important part of the Church’s overall structure and

contributor to its mission, and how their duties to enforce ecclesiastical

discipline (cc. 391-392) both depend on and contribute to their leadership in

other areas.

Canon law’s enforcement mechanisms differ profoundly from

that of any other major legal system. There are no canonical police, no

canonical jails. The direct financial power of the Church over its members is

limited to a tiny percentage of its population. Moreover, contrary to popular

perception, canon law cannot threaten recalcitrants with dire consequences in

the next life. (Well, not directly anyway.)

In a legal system, therefore, wherein physical, financial, or

eschatological coercion is all but non-existent, how do bishops enforce the law?

They do so most effectively by their own personal example of adhering to law. In

other words: Bishops must come to know and accept the operations of canon law in

their lives and ministries, in order to call, most convincingly, their subjects

to lives and works in accord with the ecclesiastical discipline by which all are

bound. A bishop who, notwithstanding only a cursory exposure to canon law many

decades before, really commits to knowing the canons affecting in his actions,

has the credibility to extend that requirement, adapted to their conditions, to

his priests, diocesan staff, parish workers, and faithful at large. A bishop who

accepts the limitations that canon law places on his own plans or preferences,

has the credibility to expect others to temper their desires in accord with that

same law. In brief, a bishop who lives with law can lead with law.

The final canon of the 1983 Code, treating dryly of some

procedural requirements to be honored in pastor transfer cases, concludes with a

remarkable crescendo, reminding bishops that “the salvation of souls, which

must always be the supreme law on the Church, is to be kept before one’s

eyes.” May the suggestions in this essay help our bishops to apply canon law

in ways ever more conducive to the good of the Church and the welfare of souls.

+++

|