|

|

|

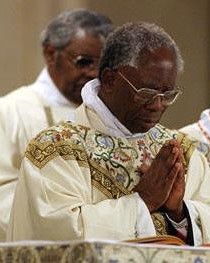

Cdl. Arinze with hands joined,

the position

normally associated with

silent priestly prayer

or with

his prayers offered

with the congregation

|

The first thing to notice here is

that, with the problematic exception of the Our Father, the orans

position is prescribed for the priest only when he is praying aloud and

alone as, for example, during most of the Opening Prayer, the Prayer over the Gifts,

and the Post-Communion Prayer. When, however, the priest is praying aloud

and with the people, for example, during the Gloria or the Creed, his hands are

to be

joined. In other words, a priest praying aloud and on behalf of a then-silent

congregation is clearly exercising a leadership role. The

orans posture being used then cannot occasion congregational

imitation because the people are silent at that point in the

Mass.

On the other hand, when prayers are

being said aloud by the priest and people, the fact that the priest’s hands

are joined during such prayers occasions — if anything by way of

congregational imitation — the traditional gesture of joined or folded hands

that is common among the laity at Mass in the West. |

From all of this, it seems that the rubric calling for

the priest to assume the orans position during the Our Father, in which

prayer he joins the people instead of offering it on their behalf, is at

least anomalous, and probably inconsistent with the presidential symbolism suggested

today by the orans position elsewhere in the

Mass.

There remains to consider, though, how

this apparent miscue appeared in the liturgy.

I suggest that originally,

the orans rubric for the priest during the Lord’s Prayer was not a

mistake but that it became one in the course of liturgical reforms

undertaken by Pope Pius XII just prior to Vatican II. Let's back up a bit.

The Our Father (Pater noster) has been

a part of the Mass for many centuries. Over that time, of course, language

barriers occasioned and rubric evolution reinforced the assignment of nearly all

Mass prayers to the priest. Eventually, the Pater became a prayer that

was offered by the priest on behalf of the people, whose exterior participation

in that prayer was, by the early 20th century, limited to a vicarious one via

the server’s recitation of the closing line, Sed libera nos a malo (But

deliver us from evil). A look at pre-Conciliar rubrics in any Sacramentary

regarding the Pater is consistent in showing that the priest’s hands are extended,

that is, in an orans position, as one would expect for prayers the priest

offers on behalf of the congregation.

But in 1958, as part of Pope Pius XII’s liturgical reforms, permission was granted for, among other things, the

congregation to join the priest in praying the Pater, provided that they

could pray it in Latin (See AAS 50: 643; Eng. trans., Canon Law Digest V:

587). Thus, for the first time in many centuries, a congregational recitation of

the Lord’s Prayer was made possible. Lay recitation of the Pater was not

mandated and there is no evidence that this very limited permission for

congregational recitation of the Pater occasioned awareness that such

permission, if it were ever widely acted upon, might necessitate a change in the

rubrics for the priest. Unfortunately, by the time such changes did come about, it seems, the orans

posture and the Lord’s Prayer had become

associated, not with the manner in which the prayer was being offered, but with

the prayer itself. From there, it seems, the rubric calling for or the priest

to continue using the orans position during the Our Father simply passed unnoticed into the new rite of

Mass.

|